I wrote this for my weekly newsletter which you can subscribe to here.

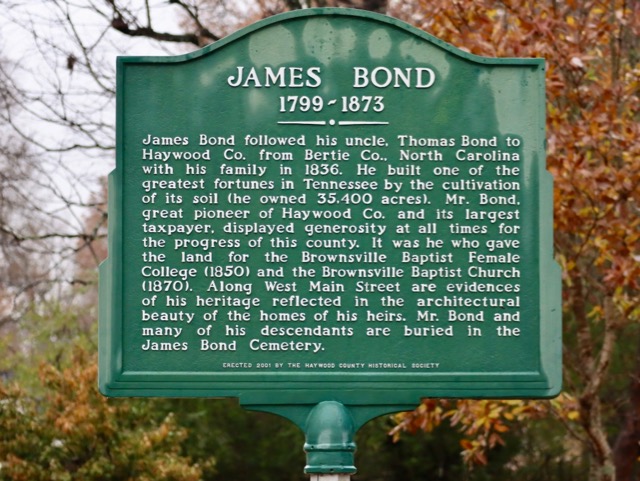

Yesterday morning I walked three quarters of a mile from my in-law’s home in Brownsville, TN to this roadside marker beside a small family cemetery.

James Bond, a quick internet search will reveal, was once one of Tennessee’s largest slaveholders.

By the eve of the Civil War, Bond had amassed property holdings in Haywood County alone of more than seventeen thousand acres and approximately 220 slaves. In 1859 his five plantations yielded more than one thousand bales of cotton and nearly twenty-two thousand bushels of corn. The federal manuscript census for 1860 estimated his total wealth at just under $800,000. (By comparison, the total value of all farmland, buildings, and other improvements in the entire county of Johnson–situated in the mountainous region in the northeastern part of the state–was just under $790,000.)

The average passerby will intuit none of this from the marker standing watch over the great pioneer’s grave even though almost nothing on that marker would have been accomplished or amassed without those women and men he enslaved.

It’s not exactly a secret that James Bond owned people; people in this town know it, or at least some of them do. But seeing a sanitized version of his legacy etched in steel does reveal something about our shared memory. After all, the choice – and it must have been a conscious decision – to gloss over the source of the man’s wealth and generosity was an act of deliberate forgetfulness.

I’m sure this sort of thing is not unique to this country. It’s one of the privileges exerted by the powerful in any society to remember history in a manner wherein our forefathers and mothers retain their heroic status. But still, there is a particular way in which we forget things in the U.S.A.

In 1962 James Baldwin published a letter to his nephew. In it, he warns his young namesake about the dangers he will face from forgetful white Americans.

I know what the world has done to my brother and how narrowly he has survived it and I know, which is much worse, and this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it. One can be–indeed, one must strive to become–tough and philosophical concerning destruction and death, for this is what most of mankind has been best at since we have heard of war; remember, I said most of mankind, but it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.

Baldwin was surely thinking about more than deceptive roadside memorials to slaveholders, but it does illustrate his point in concrete and metal.

//

The gravity of Christian worship is the Lord’s Supper when bread is broken and wine poured out. “This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me… This cup is the new covenant in my blood; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me.” (1 Cor. 11:24-25) In remembrance. There are echoes here of the many times God commanded his people to remember their former captivity and God’s saving intervention.

Forgetfulness, in other words, is not normal for Christians, at least not the willful variety. Remembering is one of the choices we can make which draws us toward our Savior and into the presence of sisters and brothers. And yes, this is a remembering that centers on Christ, but at table we also remember precisely why we come so hungry and thirsty. We remember our sins, even the ones previous generations worked so hard to forget.

This week, using this helpful site, some of us posted to social media which Native American people’s land we were celebrating Thanksgiving from. It’s true that this could easily slide into a kind of meaningless virtue signaling. But, for some, it represents a decision to remember what has been forgotten for so long that many of us hadn’t even known that it could be remembered. It’s a small decision which can remind us that forgetting isn’t inevitable.

//

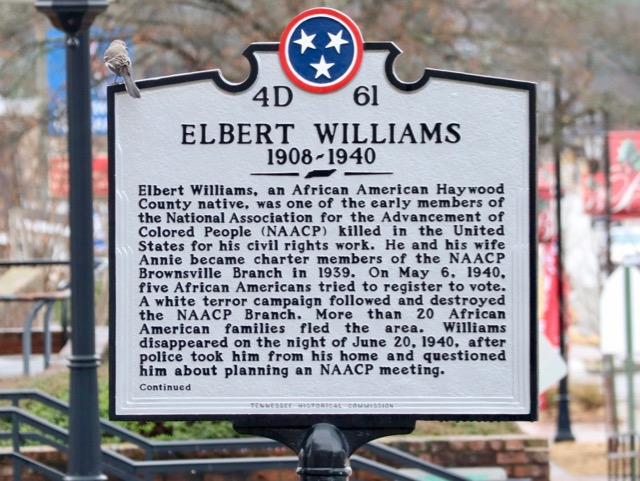

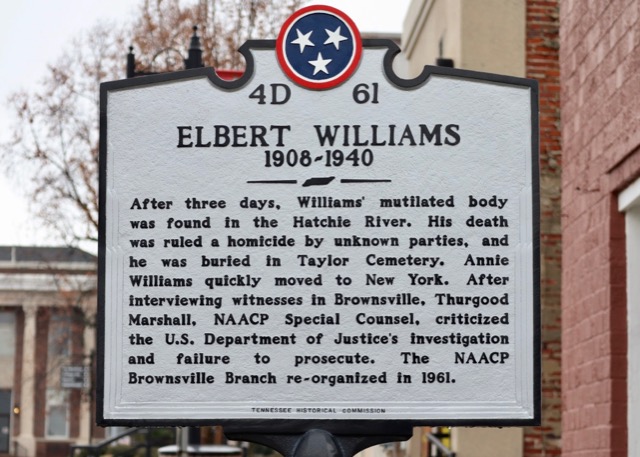

After visiting James Bond’s grave, I walked to the small town square which is dominated by a monument dedicated to “the Confederate dead of Haywood County.” There, a block away, is a recently placed monument to Elbert Williams, a man known as the NAACP’s first martyr. For his efforts to register black voters, Williams was kidnapped by the police and drowned in the Hatchie River.

I’m not sure why the Tennessee Historical Commission decided to erect this marker so many decades after Williams was lynched, but its presence is notable. Standing in the shadow of the county courthouse is this honest testimony to an ugly past and proof that, if we want to badly enough, we can remember what was previously and purposefully forgotten.

Leave a comment